You are a storyteller… sometimes

Have you seen Stefan Sagmeister’s ‘You are not a storyteller’, which recently went viral?

Because of its universal title and Stefan’s combative tone, this video is being seen as one of those ‘X is dead’ pieces that people respond to by saying ‘thank God somebody finally said this’. Its popularity suggests that people felt it was about time that ‘the storytelling thing,’ as Stefan calls it, got its comeuppance. To be honest, I think they’re reading a bit too much into it, seeing a reasoned argument in what’s actually a fairly narrow rant. But the points raised are definitely worth discussing.

Everyone’s a storyteller

On the Vimeo page for the video, Sarah Thompson posts this comment:

Every human being by nature is a storyteller – rollercoaster maker or carpenter. [Stefan’s] view is archaic, shallow and elitist. We all speak in story, we live in story. We have all been doing this for 27,000 years – starting on caves and now with tweets.

This fine democratic sentiment is true on one level, like saying everyone is creative. But if everyone is a storyteller, no one is a storyteller. As professional marketers, as opposed to anthropologists, we invoke the concept of quality because we want to know what has real effects in our world. For us, telling ‘good’ from ‘bad’ is not elitist; it’s just practical.

When people in marketing say ‘storyteller’, they don’t usually mean someone who shares the story of their sandwich with three friends. They mean someone whose stories touch thousands of people they’ve never met, with the power to persuade as well as enthrall and entertain. That’s why saying you’re a storyteller is a big deal, and why it’s irritating when too many people do it.

Let the work speak

In Stefan’s view, being a rollercoaster designer – and, by implication, anything creative – should be enough in itself. We should be proud of what we do for what it is, and not dress it in borrowed robes to boost its short-term credibility.

Certainly, there’s a danger in jumping on a bandwagon, although the crash when the wheels eventually come off is never quite as apocalyptic as some commentators would like it to be. The talented prosper whatever label is applied to them, while the pretenders fall by the wayside. And the ‘thing’, whatever it is, just carries on in a less hyped form, or under a different name (see SEO, content marketing).

There’s also a moral point here about humility; about letting your work speak for itself. To call yourself ‘storyteller’ is to take on a privileged role in society, one with almost mystical significance and authority. As Stefan says, even a seasoned novelist or filmmaker might prefer to let others decide whether they deserve the title. They might also feel that the word just isn’t relevant, or that it diminishes or even infantilises their work.

Personally, although I put as much heart and craft into into my work as I can, I find even ‘writer’ a bit too overblown for what I actually do most of the time, which is explain things to people who aren’t really listening. When people call themselves ‘storytellers’, they’re making a fairly bold statement about their work. They’re also elevating themselves far above the practical worldview of some clients – although that may be deliberate positioning, of course.

Anything can be a story

Then again, who cares what people call themselves, as long as they deliver? Maybe the real question is not whether people are really storytellers, but whether the things they make are really stories.

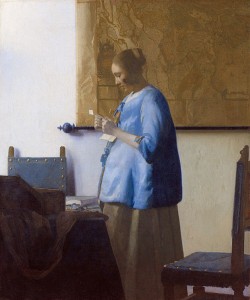

The first point to make is that anything can be a story, within its own limitations. A song, a joke, a Tweet or a TV ad can be a story, just like a novel or a drama. Even static works of art, like Vermeer’s Woman In Blue Reading A Letter, are freighted with narrative; the picture may not be ‘telling’ a story, but we’re still hearing one.

A rollercoaster could be a story too – and not necessarily a ‘bullshit’ one either. Yes, it might be a bit linear and short of characters, but it could still have suspense, development and revelation – plus excitement in spades. A rollercoaster created by Salvador Dalí would be a masterpiece. In the hands of an artist, anything can be art.

Stories that aren’t

However, most rollercoasters I’ve seen are neither stories nor art. And just because anything can be a story doesn’t mean everything is a story. But that seems to be the way we’re going in terms of how we describe our work.

Digital ‘storytelling’ is a case in point. Moving online has given marketers more room to breathe than traditional ‘interruptive’ media, while also obliging them to create content that people want to share socially. The result has been a surge of interest in storytelling, which ticks all the boxes – longform, human, shareable.

That doesn’t mean that anything and everything posted online is somehow, magically, a story. But ‘storytelling’ still seems to have morphed into a catch-all term for any sort of branded digital content that aims for social appeal or doesn’t directly ask for the sale.

Maybe it’s partly a semantic confusion, due to the elision of PR and news ‘stories’ with other sorts. But while this type of content may have some features of a good story (such as relatability), it tends to lacks others (notably immersion and drama). The result is a muddying of the waters, to the point where the word ‘story’ has become so broadly applied as to be practically meaningless. If everything is a story, then nothing is a story.

Van Dammage

For example, here’s Marketing Magazine’s David Shing on Volvo’s Cannes success with ‘Epic Split’ (full article here):

Volvo Trucks’ ‘Epic Split’, another Cyber Grand Prix winner, nailed storytelling. To showcase the stability of Volvo steering, the spot featured action star Jean-Claude Van Damme doing a perfect split between two reversing trucks. Volvo found a way to make the technology behind truck steering compelling not just to the key target audience of truck drivers, but also to a general audience.

Have a look at the ad and see what you think.

For me, this fantastic work is much less a triumph of storytelling than it is of creative thinking, casting, direction and maybe even a bit of mythology. Saying it’s all about storytelling unfairly downplays the contribution of those other disciplines.

Yes, Volvo ‘found a way to make the technology behind truck steering compelling,’ but it wasn’t storytelling, it was spectacle. ‘Epic Split’ brings us the old-fashioned thrill of astounding feats under the big top, elevated to the status of art by some fantastic copywriting and stunning execution.

Maybe I’m being too literal, but a storytelling approach to this brief would be something like this:

A driver must deliver vital but fragile medical apparatus to a hospital in time to save a baby boy who is critically ill. We see him collect the documents, nod and climb determinedly into his cab. The journey is long and hard. He presses on relentlessly, eyes fixed on the road ahead, never stopping. Wild animals dart in front of his truck; he squints into the sun; swirling snow obscures his view. We perch on the edge of our seat as he reverses into the loading bay, with pinpoint accuracy, first time. He watches anxiously as the equipment is unloaded. In the final shot we see him putting an arm round his wife’s shoulders as they watch over the baby through a window, and we realise he is the father.

I’m not saying that’s a good idea (it isn’t), or that it would make a better ad than ‘Epic Split’ (it wouldn’t). I’m saying it is actually a story, as opposed to a filmed sequence of events.

If ‘Epic Split’ had been done in a time when storytelling was not so hot as a topic, no-one would be talking about its story. But in our monomaniacal world, anything good must be story – to the point where praising good work without invoking story feels almost like a backhanded compliment.

Making movies

Stefan’s point about misguided ambition to be like other media is spot on. As marketers aspire to make content that audiences love, it’s natural that they look to other popular media for inspiration. That gives us ads that are like children’s stories, websites that invite us to share the way we do on social sites and the phenomenon of ‘brands as publishers’. With all these tactics, brands aim to harness the appeal of other forms of storytelling and make it their own.

We see this ‘wanting to be something else’ in other areas too. Ever since progress in computing power made it a realistic goal, videogames have aspired to be like films. That led to some developers bolting on passive spectacle at the expense of player agency (Uncharted). Even in top-drawer narrative games like the Mass Effect series, hero/ine Shepherd goes from making finely balanced moral and military decisions one minute to recovering from being shot by crouching behind a crate the next. In a film, such events would be risible, shredding credibility quicker than an angry Krogan.

As I’ve argued, anything can be a story within its own limitations. Videogames suffer from ludonarrative dissonance because they have to unfold their narrative within the constraints of the medium. In order to enjoy the overall experience, the audience must accept its limits and suspend their disbelief.

Commercial stories demand similar compromises. First, they ask the reader to accept the brand as a storyteller despite its transparent commercial motives. Second, they impose the bait-and-switch of transferring the reader’s attention and affection from the story to the brand. However deftly this is done, it nearly always adds something ‘extra’ on top of the audience’s appreciation of the story. The result is that people will never relate to a commercially oriented story in quite the same way as a film they’ve paid to see, or a novel they’ve bought.

Does that mean marketers should stick to literal, direct communication, and never use stories? No, it simply means they should only use them when they can do so in a natural, practical way. The better the story fits with the nature of the medium, the demands of the brief and the values of the brand, the more effective that story is going to be.

Storytellers sometimes

I agree with Stefan that it’s silly for creative people of all types to use the word ‘storyteller’ to describe what they do, or for them to call everything they make ‘stories’. But storytelling isn’t just an empty affectation or a passing fad. It’s a real and precious thing that’s been badly overexposed. We don’t need an extreme ‘story is bullshit’ backlash; we just need to use the word ‘story’ much more mindfully and precisely, so we’re clearer on what is story and what isn’t.

Whether you’re developing a game, designing an album cover or writing for a brand, there will be times when you can use story to reach the audience in a uniquely powerful way. At other times, the attempt to use story might be superfluous, ineffective or downright crass. But as long as the brief demands it, and the medium permits it, we can all be storytellers – sometimes.

Comments (3)

Comments are closed.

You don’t want to get on the wrong side of an angry Krogan!

But seriously, I agree with you that ‘Storyteller’ is too commonly used, and in

part is used merely to add a little more clout to content marketer’s roles.

Saying that, I do find it interesting how the meaning of the word ‘story’ broadens

when we apply it to marketing, and I do actually think it useful for brands to

think about themselves in such terms. Not so much as having a ‘narrative’ per

say, but more a set of values that quintessentially connects with their

customers – whether that be through the writing, design, brand story or

whatever. It’s almost as if story and narrative are becoming separate

entities.

Overall,I think we are quibbling over semantics. The definition of ‘story’ I gave above

could be replaced with hundreds of different words and still be true. For me

personally, if using ‘story’ is going to inspire brands to take action to prove

their relevancy to their customers, I can’t see it as being a bad thing.

Really interesting article by the way.

Nick

@nickbeaumont:disqus

I love the Volvo ad, hadn’t seen it. Indeed its strength seem to have less to do with storytelling than with theatre. There is a lot of uncertainty, and answers and new uncertainties unfold at a breathtaking pace, contrasting with slowly moving images and music.

I’m seeing a man with his eyes closed. The music is just accompaniment, so it’s an introduction. What is going to happen?

Sunset. Beautiful landscape. Beautiful lighting.

The man is moving a bit. He is standing on something that moves in a beautiful wide-open space, during sunset. What is it?

Something is moving in the background. He is on a road.

The man opens his eyes. I know that guy. Who is he again?

He starts talking. I know that voice.

He seems to be on a road, with a vehicle on his left and one on his right. He must be going forward. But I just thought for a moment he was going backward. I can’t tell by the background, which is too far away. Disorientation. Where are we going?

Etcetera.

The story, if there is one at all, seems to our own discovery of what the actors already know is happening. The main “plot” is a theatrical effect, the crucifix-like image of Vandamme against a cloudless sunset sky.

Great insights. Regarding the Epic Split ad, i agree that it is not itself a pure brand storytelling case (although it has elements of a good brand story). Still it can be part of a a good brand story, as being one of the many conversations of the brand with its consumers.