Games tweeters play

Eric Berne’s famous book Games People Play introduced his concept of Transactional Analysis (TA). In TA, human interactions are analysed as a series of transactions – actions and reactions, or statements and responses – that lead to particular outcomes. Some outcomes are good, and some are not.

Sometimes, transactions fall into recognisable patterns that lead to predictable outcomes. In TA, these are known as ‘Games’, and their outcomes are known as ‘Payoffs’.

Sometimes, transactions fall into recognisable patterns that lead to predictable outcomes. In TA, these are known as ‘Games’, and their outcomes are known as ‘Payoffs’.

The Payoff is usually some form of psychological validation, and Players engage in Games because they want to receive it. Sometimes, the Payoff is received by the Player who seems to have ‘lost’, but actually gets to take the moral high ground in some sense. For example, in ‘Martyr’, a parent’s unwanted advice goads their son or daughter into attacking them, for which they get the Payoff of feeling put upon and holier-than-thou.

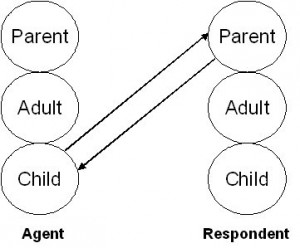

Another key aspect of TA is the way it models personality. Each of us, it suggests, has three ego-states: Parent, Adult and Child. Different states come to the fore at different times, colouring our interactions. When two Adults interact, they can progress along lines of reason and co-operation. Parent–Child dynamics (shown in the diagram) are characterised by control (Parent) and resistance (Child), or a patronising Parent and a facetious Child who’s trolling for a reaction.

Sometimes, the ostensible interaction masks another, implicit one – for example, if Black asks White to go for lunch so they can discuss their project, Black’s Adult is saying ‘let’s work together,’ while their Child is smuggling in the message ‘let’s have a drink and a laugh’.

The most confusing and destructive interactions are those where the dynamics are crossed, or asymmetrical. For example, White notes in an Adult, neutral way that the living room needs tidying. Black interprets that as a Parental nag, and their Child responds ‘Why don’t you do it yourself?’

Because Twitter is so clearly transactional (I say this, you say that), and because it’s so prone to the sort of crossed-wires misunderstanding I’ve just outlined, it throws up many of the classic games that Berne identified. Here are a couple that were brought to my mind by recent events.

‘Now I’ve Got You, You Son Of A Bitch’

In ‘Now I’ve Got You, You Son Of A Bitch’, Black commits a minor transgression, which White takes as their cue to express unlimited anger. Although prima facie the wronged party, White is secretly delighted that Black has given them an injustice to exploit, allowing them to take the moral high ground. They use their ‘trivial but socially defensible objection to vent the pent-up furies of many years’ (Penguin edition of Games People Play, p75). NIGYSOB is an Adult–Adult interaction that becomes Parent–Adult, and may devolve into Parent–Child depending on the moves that Black makes.

The parallels with Twitter are obvious. Black posts a casual or thoughtless Tweet, which is is picked up and roundly criticised by a vigilant White. At this point, Black can either back down or fight back.

If they do fight back, the Game may be prolonged indefinitely, since the remote nature of Twitter supports indefinite back-and-forth. No closure will be provided by the argument progressing to a physical confrontation, or the need to end the conversation for some external reason.

Pegged as a sexist

Recently, Simon Pegg found himself the subject of Twitter pushback from feminist writer Courtney Stoker over his sexist comment on female cosplayers.

*makes noise like Homer Simpson thinking of donuts*twitpic.com/a8myof

— Simon Pegg (@simonpegg) July 17, 2012

You may think you’re being funny,

@simonpegg, but you are objectifying geek women & discouraging more from identifying as geek.#cosplay— Courtney Stoker (@cnstoker) July 17, 2012

Pegg defended himself, and the initial round of NIGYSOB quickly engendered another, as Stoker herself was subjected to a completely unwarranted outpouring of obscene abuse from pro-Pegg tweeters. Pegg discouraged that, but refused to back down on his original comment – or, at least, to offer the apology that Stoker felt was warranted.

@cnstoker You have to address motive and my motive was neither to offend or objectify. I won’t apologise because you demand it. The end. — Simon Pegg (@simonpegg) July 17, 2012

In appealing to Stoker to ‘address motive’, Pegg makes a case for Twitter as pub, rather than publication. Increasingly, however, we’re seeing Twitter feeds treated as texts rather than ragbag collections of thoughts – texts that are fair game for analysis, wider reporting and even legal proceedings. Pegg did eventually post a rather passive-aggressive apology ‘to any I did offend’, while Stoker posted a Storify documenting her side of events.

For the record, I agree with Stoker that Pegg’s remarks expressed a casual, institutional sexism, and that men shouldn’t get to set the terms of the gender debate by deciding (perhaps in retrospect) what is ‘not really meant’ or ‘just a bit of fun’. But I also agree with Pegg that, in a democracy, it’s up to him to decide whether and how he renounces his own mistakes.

For me, the real point is the way Twitter seems to facilitate or even encourage the playing of NIGYSOB. I’m not characterising Stoker as a ‘humourless militant’ (as Pegg did), because we all fall into the same trap when our buttons are pushed. Having researched gender and cosplay, Stoker was always going to have an opinion on Pegg’s tweet.

For me, typical trigger points are people being rude about Birmingham, where I was brought up, or posting ill-informed comments about social care for children (my partner’s profession). And because I fancy myself a contrarian, I often have to bite my lip when people parrot the same old stuff about marketing and social media. For any of us, being straight-out insulted by a stranger is an obvious starting point.

The problem is, as I’ve noted, is that there is no easy way to end the confrontation once it starts. In person, an argument between strangers is such an explosive situation that it either blows up or is defused by onlookers. Online, no-one’s going to get punched, and most bystanders are discreetly savouring the ding-dong, so we just go round and round forever.

@cnstoker Still, it was not my intention to offend and I am against the objectification of women when the intention is malicious. Chums?— Simon Pegg (@simonpegg) July 17, 2012

Attempts at reconciliation, like Pegg’s hopeful ‘Chums?’ can be rebuffed in a double-or-nothing tilt for the full-blown apology. The result is an excess of strong feeling without any corresponding sense of release.

‘Ain’t It Awful’

If others weigh in on White’s side, the Twitter version of NIGYSOB can morph into an intense round of ‘Ain’t It Awful’ (p96). AIA is all about wallowing in the worst of the world; its tagline is ‘Misery Loves Company’.

Adults at a party may play the ‘Nowadays’ variant, where things are never what they used to be. Work colleagues are more likely to go for ‘Water Cooler’, which focuses on whatever ‘they’ are doing to ‘us’ now.

On Twitter, AIA becomes a mass outpouring of disapproval that masks a shared sense of virtue – expressed by the famous TA phrase ‘I’m OK, You’re OK’. By sharing our distaste for a carefully chosen ‘other’, we reinforce the social bonds between our own group.

That’s the bad guy

The ‘it’ that is ‘awful’ varies widely. In my own circle, it’s very often a Daily Mail article, most probably written by Samantha Brick. At other times, it’s been phenomena as varied as Trafigura, Iran and Ryan Giggs. During the Olympics opening ceremony, it was Aidan Burley’s ‘multicultural crap’ tweet.

Thank God the athletes have arrived! Now we can move on from leftie multi-cultural crap. Bring back red arrows, Shakespeare and the Stones!

— Aidan Burley MP (@AidanBurleyMP) July 27, 2012

By playing the panto Tory, Burley was actually performing a valuable public service: bringing some much-needed moral saltiness to Danny Boyle’s sugary love-in. If no-one is on the outside, how can we be sure we’re on the inside? Or as Tony Montana put it in Scarface, ‘You need people like me. You need people like me so you can point your f—in’ fingers and say, “That’s the bad guy”.’

Rounds of AIA on Twitter can be sustained by the most desultory means. An automatic RT takes just two clicks, allowing the participant to express their agreement without adding any original expression of their own. Many tweets are transparently written to elicit this sort of mass conformity, whether or not they explicitly invite it (‘RT if you agree that…’).

AIA is always predicated on distortion. Instead of seeing others as fallible humans like ourselves, we judge them by the harshest standards and condemn them without a trial. On Twitter, the game can be predicated on a single tweet, allowing players to characterise someone as ‘bad’ without the burdensome chore of actually getting to know them and weighing the different aspects of their personality.

AIA is a Pastime rather than a Game, because it lacks closure and has no real payoff. Players simply compare notes until they lose interest or start to feel oppressed by what Berne calls ‘unworthy feeling’. On Twitter, AIA usually continues until a new ‘controversy’ is manufactured; there may be several ‘scandals’ each day.

Beyond Games

In Berne’s worldview, Games are not always trivial, despite their name. Some are played for very high stakes, last many years and end in violence, prison or death. But whatever their Payoff, they are all manifestations of dysfunction. If we find ourselves playing Games compulsively, we need to find a new, more productive way of interacting with those around us.

Twitter presents us with an un-human distortion of natural emotional processes, enabled and exacerbated by technology in a way that no-one could really foresee. And, unless we renounce our social media, it seems we’re stuck with it. So we have to decide how we’re going to deal.

In most cases, the key is to keep interactions on the Adult–Adult plane. That means choosing our words, picking our battles and knowing when to stay silent. It means knowing ourselves well enough to recognise when we are having our buttons pushed (or pushing them ourselves). And it means accepting that if we want a channel that reflects everyone’s thoughts at the moment they have them, we’re going to have to let a few things slide.

Sometimes, it seems to me that Twitter started out as a community of Adults, but is devolving into a mass of Parents and Children. If we want to preserve its value as a social forum, we need to make sure it’s about more than playing Games.