The mistake is the message

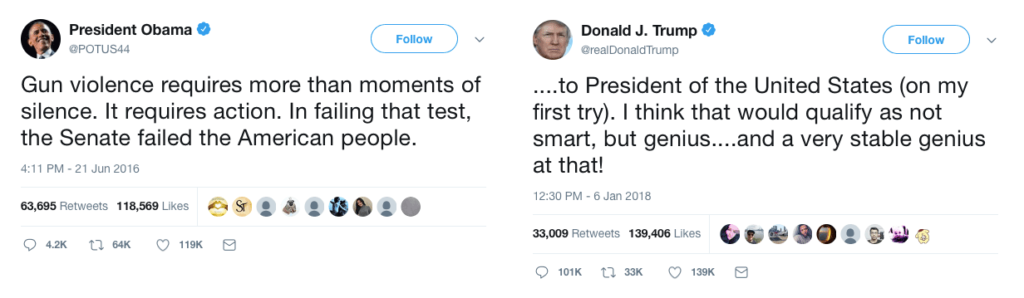

I’m fascinated by the revelation that Donald Trump’s aides deliberately mimic his grammatical mistakes when composing tweets on his behalf.

If that’s true, it makes perfect sense. Trump himself was never going to submit to an editor, or memorise a style guide. The only way to make his feed remotely consistent is for others to imitate his style.

That style is pretty terrible, particularly in comparison with Trump’s predecessor. But so far, Trump has hardly suffered as a result. In fact, he’s weaponised his illiteracy, turning it into a potent, multifaceted communication tool.

Trump’s messages go direct to his base, who applaud his linguistic trolling, don’t notice it or simply don’t care. He speaks their language.

Meanwhile, his mistakes infuriate liberal intellectuals, diverting them into debates over detail. And of course, our ridicule only makes him stronger. Trump’s Twitter is a weapon of mass distraction.

Grocers apostrophe’s

How important is it to get grammar, spelling and usage right? My answer is that it depends on who’s writing.

A while ago, I decided to stop scoffing at everyday writing mistakes online, just to get likes and shares.

This isn’t about words; it’s about people. That ‘bad’ writing you’re sharing is the best someone could do with the resources they had. Maybe, despite their best efforts, they haven’t mastered every intricacy of the English language. Maybe they have some form of dyslexia, as 1 in 10 UK adults do. Maybe they’re one of the 1.5m UK people with a learning disability. Or maybe they have no disabilities, but were simply busy, tired, bored, distracted or upset when they were writing, and they made a mistake. Have you ever made a mistake?

You get the point. Pointing out mistakes is ableist, snobby and unedifying. It doesn’t really help anyone. And in nearly every case, it’s perfectly clear what the writer meant anyway.

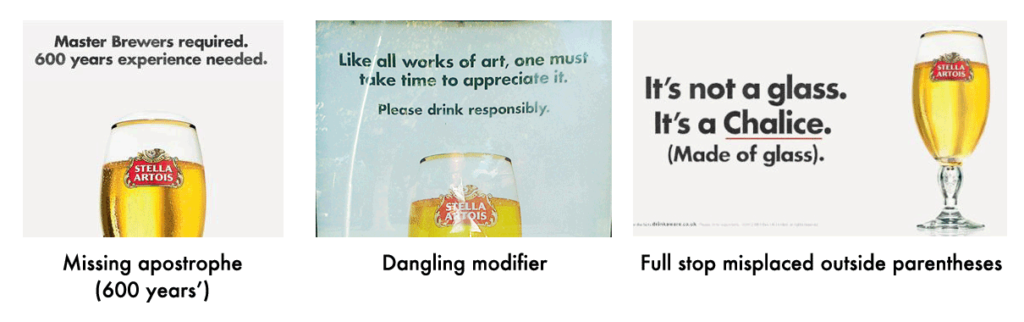

However, I would argue that it’s different for big brands. With far more resources at their disposal, they should be able to avoid errors like these three from Stella Artois (discussed in more detail here):

These aren’t deliberate provocations; they’re just mistakes. We can be sure of that because they’re so at odds with Stella’s tone of voice. No brand that used taglines like ‘Reassuringly expensive’, ‘She is a thing of beauty’ and, er, ‘Be legacy’ would deliberately make errors that flew in the face of its own values (culture, quality, sophistication).

Deliberate mistakes

For other brands, though, ‘wrong’ language could be absolutely right. The question isn’t what is correct, but what works. The advice I give in my book is that ‘if you have to choose between being clear and correct, be clear’.

So, could brands make technically ‘wrong’ language a regular part of their communications? Could they use mistakes to define a voice, cut through the noise and build engagement, just as Trump has?

It’s not so far-fetched. In fact, it’s logical. If brands have tones of voice that are carefree, cheeky or childlike, why shouldn’t they make mistakes too? Given literacy rates across the population, you could even argue that accuracy is actually off-brand if you want to strike a universally inclusive tone. While broadcast media have loosened up – particularly for young audiences – brands cling to the standards of a 1950s BBC announcer.

One classic example of a brand breaking the rules is ‘Beanz Meanz Heinz’.

However, I’d argue this is a form of poetic licence. Maurice Drake consciously took the sound and spelling of ‘Heinz’ and extended it, to brilliant effect. But while the slogan has the feeling of a child’s error, it doesn’t really look like a real-life mistake. It’s a stylised transgression.

More recently, last April Fool’s Day, Lionsgate promoted the film Ghost Stories with some deliberate errors, such as a poster for ‘Ghost Storeis’ that proclaimed ‘the brain sees waht it wnats to see’.

Again, this is less a mistake than a metatextual prank. The ‘errors’ are there to underline the message of the tagline; if you don’t even realise they are errors, you miss that part of the meaning completely. So the target audience is people who are literate enough to get all that, rather than those who write that way themselves.

These examples are interesting, but they’re outliers. Could we see a more general relaxation of language rules, so what is wrong today is right (or at least accepted) tomorrow?

I got new rules, I count ’em

The idea of ‘correctness’ in language is relatively recent. The first known English grammar book, modelled on Latin, was written in 1586. Over the next 250 years, many rival authors put forward their own take on what was ‘right’. Only in the 19thcentury was language studied systematically.

Rules depend on enforcers. Publishers and editors, the gatekeepers of old media, controlled who said what in print, and how. But new media puts the means of textual production in everyone’s hands. As a result, prescriptivist grammar is under assault from a deluge of acronyms, neologisms, abbreviations and memes.

As Pete Hess’s recent post on ‘Sunsetting Klout’ shows, businesspeople often want to imply that new words equal new thinking. Even mistakes can become words – like ‘pwn’, which started out as a typo and has become indispensable to a particular culture.

Progressives believe in progress. (The clue’s in the name.) But faced by Trump, Putin and Orbán, we have to ask ourselves whether things we thought were established – like truth and democracy – might actually be melting away. And, in the same way, maybe what we call ‘correct’ today is actually just one brief chapter in the life story of language. Everything changes.

Not better, but different

Obviously, I hate all this. I’m a professional writer and editor, I have an English degree and I’ve read (cough) some books. I love the English language, I love good writing and I really care about getting it right myself. But that’s kind of the point.

Sticklers for correctness are easily derided as elitist snobs or ‘grammar nazis’. But while the caricatures are absurd, there’s a grain of truth to the accusations.

We may not be claiming superiority, but we’re still claiming difference. Technical language skill defines an in-group (those who can get it ‘right’) and an out-group (who get it ‘wrong’). ‘Loving’ and ‘caring’ about language expresses the desire to be part of the in-group; pointing out mistakes reinforces and condemns the out-group. ‘Rightness’ is a concept that we mobilise so we can bolster our own authority as experts. In other words, language competence is tribal.

The day might come when we have to choose a side. What language will we use for the brands we serve, or the causes we care about? If the language of the people is ‘wrong’, should we speak it too? At the end of the day, do we want to be right – or do we want to be heard?