The pros and cons of scary copywriting

To celebrate Hallowe’en, I thought I’d focus on the pros and cons of scaring your readers as a copywriter.

Negative copy focuses on bad things that will happen if people don’t choose a particular product, service or course of action. The sell is predicated on the idea that the consequences of not buying will be distressing, embarrassing or otherwise undesirable. We might call these potential outcomes ‘negative benefits’. Copywriting driven by negative benefits points out a problem that the customer has, before positioning the product or service being promoted as the solution to that problem.

Whole product lines have been driven by this kind of copy plot. As Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner recount in Freakonomics, Listerine brought a completely new problem – ‘chronic halitosis’ – to the public’s attention while simultaneously offering the solution. The fact that Listerine’s marketers had invented the faux-medical term didn’t hold back the campaign or the product. Nowadays, the sell for such products tends to be more positive – we buy in order to have fresh breath, rather than to avoid bad breath.

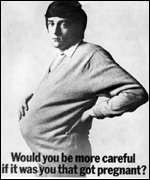

Negative benefits don’t even have to be real to be effective. Saatchi & Saatchi’s famous ad from the 1970s asked ‘would you be more careful if it was you that got pregnant?’ The question is rhetorical but still thought-provoking, which was surely the intention.

In most cases, there’s a choice to be made between selling on a positive or a negative. Insurance can be presented as obtaining peace of mind (positive) or avoiding financial crisis (negative). Even classic ‘distress purchases’ – those that we make because we have to, not because we want to – can be positioned positively. For example, buying sticking plasters could be portrayed as part of being a good parent. Or there may be the opportunity to stress some benefit that mitigates the distress of the purchase, as with one-coat paint or similar convenience products.

So, is it ever right to focus on the negative? Personally, I think the scare tactic needs to be used with great care. You’re evoking negative associations and banking on the reader taking the next step to the solution that you’re offering – rather than simply walking away before you even get to make your pitch. I once saw an ad for a will-writing service that described the problems of dying intestate in such apocalyptic terms that it was a complete turn-off. It made it sound like the taxman would take every last penny and your family would end up on the street. The aim was to cultivate a healthy fear of financial chaos, but the copy went too far and ended up generating resentment and irritation (in my mind anyway). As ever, there were positive aspects that could have been emphasised instead – being organised, helping relatives and so on. In most cases, it’s probably less risky to associate your product with positive feelings and enjoyable outcomes that will mean something to the customer.

The exception may be products that solve a well-known or long-standing problem that the customer will definitely recognise and be interested in solving (as opposed to one they’ve never thought about before). An example would be online comparison sites that offer to take the hassle out of buying insurance, holidays or other items where the choice is very wide. Here, people are well aware that buying can be a chore, making the task of the copywriter far easier – there’s no need to explain the problem before offering the solution.

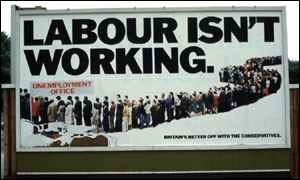

The problem you offer to solve shouldn’t include using a competitor’s product, no matter how inferior that product is in reality. Comparative advertising or ‘knocking copy’, which actively criticises a rival offering, is another high-risk tactic. However, it’s one that can work in the right circumstances, as Saatchi (again) proved with ‘Labour isn’t working’.

Most modern ads, if they choose this tactic, opt for (say) a comparison table that purports to let the facts speak for themselves. Of course, the advertiser is controlling the game by choosing the areas for comparison, but this can give the impression of being impartial – or at least factual.

However, mentioning your competitor is dangerous for two reasons. Firstly, it’s an invitation for the reader to start thinking about the competitor rather than you. If they’re not paying careful attention, it might be the competitor’s brand that sticks in their head, not yours. In a way, you’re inviting them to check out your competitors before making a decision. Or, if they’re already using a competing product, your pitch implies a criticism of their choice. Telling the customer they’re in the wrong is rarely the way to close a sale. By contrast, offering to improve their situation is a great opening offer. So it’s better to focus on what you can do for the customer, not what a competitor can’t.

Comments (3)

Comments are closed.

Yes, I agree – the positive is generally the best bet. Negative ads are also likely to inspire retaliation from your competitors.

On the other hand, you can create ads that are so insanely negative or offensive that the indignation they rouse gets acres of free publicity. This is something that has to be handled with extreme caution, though – the Labour poster of Michael Howard swinging a watch and looking like Shylock didn’t do anyone any favours, and I bet it lost more votes than it won.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Lorraine Thompson, Ben Locker. Ben Locker said: RT @ABC_Copywriting: RT @tweetmeme The pros and cons of scary copywriting http://retwt.me/1G8oj […]

Thanks for such an interesting blog. I think positivity wins just about every time. Drayton Bird cites the example from a book about advertising by Max Sackheim who co-founded one of the first direct marketing agencies. Sackheim wrote 2 ads in the 1890s selling washing ‘machines’ to women. The smiling face and the line ‘Let this machine do our washing free’ trounced the alternative with the sour face and the “Are you chained to the wash tub?” headline. Ancient ads and woefully unsophisticated to our eyes but, as John Caples said, again many decades ago, “times change, people don’t”. The ad world has changed beyond recognition of course but the same principles about human psychology apply.