Why marketing is evil

Are we approaching the final battle? Some think so, regarding movements like Occupy as the first stirrings of popular resistance to the capitalist system. Our comfortable Western world is going to be shaken by tectonic shifts in the global economy and the environment, and the result will be huge social upheaval as the old order passes away and a new one is instated.

I find Occupy bracingly idealistic, and at the same time laughably naïve. We should certainly question the system in which we find ourselves, but it’s not as simple as being for it or against it. We are all complicit. The issues are too universal to be reduced to class or generational conflict, which is the territory where movements like Occupy tend to end up. The rhetoric is a powerful motivator, but can obscure the very complexities we need to address.

Having said that, we do all have choices to make, and one of the most important is the work that we do. So where does marketing fit into the picture? Can one be a marketer and also on the side of progress? Is marketing part of the solution, or part of the problem?

Case for the prosecution

One way late-stage capitalism sustains itself is by driving overconsumption. Once markets mature and competition intensifies, it becomes increasingly difficult to sell people more stuff and secure the holy grail of growth. Over time, goods tend to become commodified – that is, broadly similar to each other, with price the only factor in a buying decisision.

Firms respond, in part, with novelty: making things new again, and cultivating the desire for them afresh. We can see this very clearly in cultural industries such as fashion and pop music, where new looks and acts appear each season. However, in recent decades the same philosophy has invaded the supermarket aisles. More and more new products are launched, while existing ones are endlessly reinvented and repackaged so they can be repositioned as ‘new and improved’, or a subtler variation on the same message. In the B2B arena, we see a similar phenomenon under the catch-all banner of ‘innovation’.

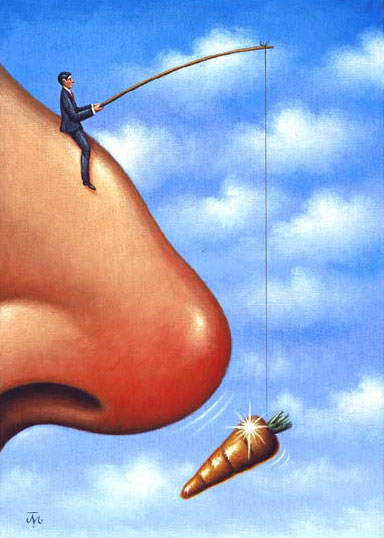

To convince people to buy their new stuff, firms turn to marketers. On one level, marketing is simply the channel through which they inform people about their products. But it is also marketing, considered in its broadest sense, that gives a physical product or service its aura of desirability. As marketers, we craft the messages and images that (we hope) convince people they need a particular product in their lives – either instead of, or as well as, some other product.

If changes are indeed coming to our society, one of the most significant might be a radical downsizing of material expectations. We may have to make do with less, in many ways: lower incomes, part-time hours, fewer holidays, later retirement, smaller carbon footprint and so on. In other words, we’re going to buy less stuff.

Marketing encourages the precise opposite, cultivating behaviours and mindsets that are completely at odds with the way our society is heading. It cultivates desire, fuels dissatisfaction and drives overconsumption; it can only encourage us to buy more.

Overconsumption isn’t just a moral or psychological problem. It has many real-world impacts. At the personal level, it stops us building up a savings ‘cushion’ that would protect us from economic chaos or reduce our dependence on work. It diverts resources away from progressive actions we could take, such as giving to charity or simply refraining from spending. If we get sucked into the cycle of ‘getting and spending’, it upsets our work/life balance. And at a more universal level, it accelerates the destruction of the environment and reinforces the acquisitive, materialistic side of our culture. When we overconsume, we invest in the present rather than the future – in a very literal sense, we buy into the status quo.

Overconsumption isn’t just a moral or psychological problem. It has many real-world impacts. At the personal level, it stops us building up a savings ‘cushion’ that would protect us from economic chaos or reduce our dependence on work. It diverts resources away from progressive actions we could take, such as giving to charity or simply refraining from spending. If we get sucked into the cycle of ‘getting and spending’, it upsets our work/life balance. And at a more universal level, it accelerates the destruction of the environment and reinforces the acquisitive, materialistic side of our culture. When we overconsume, we invest in the present rather than the future – in a very literal sense, we buy into the status quo.

Seen in this light, marketers are not agents of change in a deep sense. We may fetishise novelty, but ultimately we shuffle the pack without changing the game. By encouraging consumption and spending, we keep people stuck in the groove where capitalism wants them to be. Basically, we’re not helping.

The libertarian defence

The argument that marketing or advertising harms society is not new. When it is wheeled out (which happens regularly, as in this crusading George Monbiot piece), marketing professionals usually respond with a well-practised line centred on freedom of speech and freedom of choice. We live in a democracy. Marketers are free to say what they want, and consumers are free to buy what they want. And besides, who will decide what’s fair, and what isn’t? Left-wing newspaper columnists?

The most advanced and nuanced form of this argument that I have seen is proposed by Jeremy Bullmore in his essay Competitive Persuasion. He cites the democratic system of government, and the adversarial system of justice, to argue that ‘competitive persuasion’ is the best way we have of presenting alternatives and allowing the ‘audience’ (voter, juror, consumer) to ‘read, absorb, reject, modify – and make up [their] own minds’.

Challenging the complaint that advertising should be ‘balanced’ or ‘more truthful’, he presents this magnificent summary of the ‘free choice’ position:

I believe that competitive persuasion leads to a discriminating, alert, intelligent society in which each member can arrive at his or her own decisions – whether or not they seem rational, sensible and correct to any self-appointed protector.

Note how far Bullmore is going with this. For him, it’s not just a question of marketing not being harmful – he’s actually suggesting it’s an active force for good. It keeps society, and the individual, sharp. If it did not exist, he implies, it might be necessary to invent it.

Expressed so eloquently, the libertarian argument takes on an almost Classical symmetry, as if it were some sort of natural law. But seductive ideas are not necessarily right. As Paul Krugman noted, reflecting on economists’ failure to predict the financial crash of 2007:

The economics profession went astray because economists, as a group, mistook beauty, clad in impressive-looking mathematics, for truth… economists will have to learn to live with messiness.

The truth is that we all have to live with messiness – and we can’t use highflown ideas to excuse the manifest consequences of our actions.

Unequal power

The natural law that Bullmore’s competitive persuasion most resembles is natural selection. Equal players duke it out on a field that is the same for all; the strong prevail and the weak fail. As a result, the community as a whole grows stronger over time. No external authority, whether God or the ASA, is required to regulate the system.

This is an ‘in principle’ argument, suited to an idealised democracy populated by equal actors with equal power and equal rights. But even though we may be equal in law, or philosophy, we are not equal in reality. As Adam Curtis argued in All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, the ‘balance of nature’ is only a theory: in reality, ecosystems are in constant flux and there is no such thing as a ‘self-regulating system’. Macroeconomic events since 2007 have comprehensively demolished the laissez-faire concept of the benign ‘hidden hand of the market’, but many still cling to it for ideological reasons.

This is an ‘in principle’ argument, suited to an idealised democracy populated by equal actors with equal power and equal rights. But even though we may be equal in law, or philosophy, we are not equal in reality. As Adam Curtis argued in All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace, the ‘balance of nature’ is only a theory: in reality, ecosystems are in constant flux and there is no such thing as a ‘self-regulating system’. Macroeconomic events since 2007 have comprehensively demolished the laissez-faire concept of the benign ‘hidden hand of the market’, but many still cling to it for ideological reasons.

In nature, the economy and society, power is unevenly distributed. The mark of civilisation is that we can and do intervene to help the weakest among us. Only the staunchest conservative advocates removing the safety net of social security. The rest of us understand that society will not regulate itself, and that it is weakened, not strengthened, when it neglects those in need.

Powerful speakers, susceptible listeners

Power is unequal in culture too. In terms of marketing communication, the result of inequality is that some ‘speakers’ are much more powerful than others. It’s not a question of ‘each member’ of a society using their individual voice, but about powerful, extensive alliances crafting the most insidiously persuasive messages they can – then using vast resources to hammer those messages home as forcefully as possible.

Similarly, some ‘listeners’ are more susceptible to commercial messages than others. Try watching a commercial TV channel with a five-year-old for half an hour and you’ll soon have first-hand proof. If they’re bright and inquisitive, you might also have to explain what adverts are for, using their vocabulary – which is a truly sobering experience.

But it’s not just kids. Consider the effect of cynically alarmist ads on the worried elderly, or how anorexic women feel when they look at stick-thin clothes models. And what about viewers with dementia, or learning difficulties? As in many other areas of life, it’s easier not to think about it.

Of course, the outcome of exposure to advertising may not be a purchase; the little girl might not get her Lelli Kelly shoes, however much she asks. But the absence of a financial transaction doesn’t mean we can take comfort that the ad ‘didn’t work’ or ‘had no effect’. Indeed, this is precisely the point of what is usually called ‘brand-building’ – to lay the psychological foundations for a purchase, or cultivate latent loyalty, even if there is no immediate decision to buy.

Of course, the outcome of exposure to advertising may not be a purchase; the little girl might not get her Lelli Kelly shoes, however much she asks. But the absence of a financial transaction doesn’t mean we can take comfort that the ad ‘didn’t work’ or ‘had no effect’. Indeed, this is precisely the point of what is usually called ‘brand-building’ – to lay the psychological foundations for a purchase, or cultivate latent loyalty, even if there is no immediate decision to buy.

It’s disingenuous for marketers to say people can ‘just ignore’ their messages. Humans aren’t robots; we always respond to what we see and hear, even if only in thought. The effect of seeing an ad and ‘ignoring’ it to the best of our abilities is not the same as not seeing it at all. And advertising is more and more pervasive; we very often encounter it against our will, in an increasing number of situations.

To sum up: we should all be free in principle to say what we want, and ignore what we want. But resources matter, as do circumstances; the playing field is not level. In a world of entrenched inequality, to champion freedom is to endorse vested interests.

The neutral-channel defence

The next line of defence is the idea that marketing is a tool: a means to an end, not a ‘thing’ in itself. As a neutral channel, it can’t be held accountable for the uses or abuses to which people put it.

That’s the argument put forward in this piece by Ed Gillespie (which responds to the Monbiot article cited above). As he says:

Advertising in itself is not evil. It is just communication. As I think a former campaign director at Greenpeace once put it: “Creative communication is like a kitchen knife – you can use it to prepare a beautiful, delicious meal. Or you can use it to stab your wife.” We can use influencing techniques with insight and integrity to inspire a better world. Or we can use them to flog catfood. But it is a choice.

As with Bullmore’s ‘each member of society’, the argument is seductively symmetrical. It sounds like it should be right. In terms of its logic, it’s rather like the gun-lobby line that says ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’. Or, as Morpheus puts it in The Matrix, ‘everything begins with choice’.

However, the phrase ‘just communication’ is deeply disingenous. We come back to the issue of inequality, circumstance and control of resources. You and me chatting in the pub could feasibly be described as ‘just communication’. A multi-million pound ad campaign for SUVs is not ‘just communication’; it differs by nature, not just degree. If you can buy a gun, and I can buy a gun, we can have a duel. But if I can afford to hire an army and buy them all guns, and you can’t, the result will be a massacre.

However, the phrase ‘just communication’ is deeply disingenous. We come back to the issue of inequality, circumstance and control of resources. You and me chatting in the pub could feasibly be described as ‘just communication’. A multi-million pound ad campaign for SUVs is not ‘just communication’; it differs by nature, not just degree. If you can buy a gun, and I can buy a gun, we can have a duel. But if I can afford to hire an army and buy them all guns, and you can’t, the result will be a massacre.

Similarly, the rhetorical ‘we’ conceals the devil in the detail. ‘We’ as a collective society do have a ‘choice’ in a philosophical sense. But that choice is only enacted at the level of corporate entities who use marketing services. Do they generally ‘use influencing techniques with insight and integrity to inspire a better world’? Well, some do, but most don’t. (Although they’d probably claim that they do.)

If marketing really is just a tool, then anyone can use it, including ‘good’ organisations like Greenpeace. But ‘bad’ ones with bigger cash piles (News International immediately springs to mind) can use it far more powerfully and extensively. He who pays the piper calls the tune, and marketers are pipers extraordinaires. We follow the money – and if we don’t, we know that someone else will, so at the end of the day the societal outcome will probably be the same.

The supply-and-demand defence

A similar defence is that marketers simply connect supply (goods and services) with demand (purchasers). People want lots of things they don’t have, or haven’t heard of yet, and we just hook them up. We are selfless servants; vectors of others’ desires.

That might make sense to an economist, but not to a marketer. Any self-respecting adman knows that advertising derives its powerful emotional charge from the generation of demand: making people want something by aligning or allying it with a particular emotion.

Here’s how Richard Layard puts it, considering the impact of advertising on happiness:

Advertising is clearly meant to change our values – how we like one product compared with another. But does the advertising experience make us happier? If advertising simply provided information, it would be hard to object. But a lot of advertising makes us feel we need something that we previously didn’t need. The advertiser may have only wanted us to buy his brand rather than another. But the overall effect is to make people want more.

The most common advertising device is to show us that people of our sort have this thing – on the assumption that we will want to conform. The advert becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. The most serious effect is on children… [who] get the idea that they need this vast array of spending just to be themselves.

Richard Layard, Happiness, pp160–161

The product itself must offer some sort of benefit, of course – marketing isn’t a magic wand that can sell snow to Eskimos. But once you have an OK product, the way to shift it is by convincing people they can’t live without it. It would be a foolhardy marketer who just put the features of the product out there, in the expectation that the market would do the rest. Once we get beyond basic necessities, making a sale means generating demand.

Granted, the customer may feel that the product fulfils a need that came from themselves. But the whole affair is predicated on and motivated by companies’ thirst for profit – not some sort of altruistic quest to bring people things they somehow need or deserve.

The aesthete’s defence

Having covered the main moral and philosophical points, we arrive at what we might call intellectual coping strategies – things we tell ourselves to sleep better at night.

The aesthete plays up the creative side of marketing in order to position it as an art form. ‘I know we’re cogs in the machine,’ they argue, ‘but look at the beautiful things we make.’ For the aesthete, marketing’s potential to entertain, edify or otherwise enrich our culture can outweigh, or at least mitigate, its deleterious effects. Their stance is implicit rather than explicit; we can infer it from behaviours such as pursuing their craft (writing, photography, design) as a hobby, or curating a tumblr of ‘great work’. At a communal level, awards and awards ceremonies are a godsend, offering validation and the reassurance of a like-minded peer group.

Can we separate the art of marketing from the commerce? I don’t think so. Even though awards usually focus on the inherent merit of an ad rather than the results it generated, we can’t escape the underlying motivation. Advertising clients are not like painters’ patrons, generously supporting the creation of beauty. They’re paying to shift unit by any means necessary, and creatives are grist to the mill – like idealistic writer Barton Fink being mercilessly co-opted by studio boss Jack Lipnick and forced to write wrestling movies.

But we can’t take comfort from our oppression. Without the discipline of the brief and the commercial goal, advertising is shallow and facile – little more than intellectual masturbation. For proof of this, check out the wilder fringes of the Chip Shop Awards (entries need not necessarily have ‘run’, or even been commissioned by a client).

Of course, there may be aspects of marketing that have aesthetic value in themselves: the writing, the photography, the typography. But those things would be beautiful anyway. Marketing can’t take the credit.

‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’ as Keats put it. Marketing may or may not be truthful, and even when it’s beautiful, there’s always something else besides. Strip away the cleverness and the core mechanic is a sort of psychological bait and switch, designed to convert an audience emotion (intrigue, amusement, recognition, self-regard) into desire. From this perspective, marketing is closer to pornography than it is to art.

In James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus proposes an aesthetic theory that distinguishes between two types of art. Intellectual or ‘high’ art induces a state of static reflection, while physical or ‘low’ art is kinetic, producing feelings of revulsion (‘away from’) or desire (‘towards’). Marketing, with its ever-present motive of pushing the reader towards a purchase, can only aspire to be low art – at best.

The scholar’s defence

This defence consists of concentrating on the theory and practice of marketing to hollow out a little space where the marketer can live at one remove from commercial reality. The scholar keeps his eyes down on his work, so he doesn’t have to look up at its consequences. (It’s basically what I do on this blog.)

‘I’m really more interested in how and why things work,’ postures the scholar. ‘Others may profit from what I do, but I’m all about the ideas behind it.’ The marketing scholar is generally more realistic and reflective than the aesthete, which may be why more experienced creatives gravitate towards this persona as they age. At the extreme, they can become a contrarian – someone so secure in their beliefs and/or income that they can bite the hand that feeds (or at least pretend to).

We might also add two more personae that are common to every walk of life: the careerist, who regrets the negative consequences of their actions but still looks out for number one, and the out-and-out cynic, who just doesn’t care.

What might change?

The case for the prosecution is powerful, but the jury is unlikely to convict. Marketing isn’t going away. So what can we do? What about changing the system from within? Couldn’t we just be a bit nicer, a bit less manipulative?

Futerra, the agency run by Ed Gillespie (who I quote above), states that its mission is ‘to make sustainable development so desirable it becomes normal’. That’s laudable, and I would much rather Futerra existed than not. It is a force for good. But it is still dependent on paying clients. If businesses did not see value – commercial value – in the concept of sustainability, they would not be paying to communicate it. Marketers are not in the driving seat; even the worthiest piper is still a piper.

In fact, it’s hard to see how marketing as we understand it could be a force for genuine progress in society; the best thing would be for talented and powerful marketers to renounce their profession.

So we’ll just have to wait for our clients to change. But that’s a slow and arduous process, because as soon as progressive ideas enter the capitalist arena, they’re instantly corrupted and co-opted by The Man and turned into weapons of profit.

If the financial crisis of 2007 and its aftermath taught us anything, it’s that we will be waiting a long time for big businesses like banks to take true social responsibility. The best we can hope for is ‘caring capitalism’, where an ‘ethical’ business like The Body Shop deigns to invest some of its profits in social projects. But even this is profoundly cynical; the motive is less on altruism than on burnishing public image to gain a competitive edge. Marketers play their part by blurring the line between value and ‘values’, converting positive actions into bankable brand equity.

Why I wrote this post

You’re probably wondering why I wrote this piece – gnawing on the hand that feeds for several thousand words. The main reason is that I know, deep down, that I can’t really reconcile my political beliefs with the work I do. Most of the time I just try not to look at the elephant in the room, or I draw comfort from telling myself that I agree with the robust pro-marketing opinions I see on the internet. Just this once, I thought I’d make the effort to explore the arguments for and against – and, I have to say, I’m not heartened by what I’ve discovered. Looks like I’m one of the bad guys…

Comments (21)

Comments are closed.

“I know, deep down, that I can’t really reconcile my political beliefs with the work I do.”

I have two rules when it comes to my work Tom.

1) Never, EVER compromise my principles

2) I can’t afford to have principles

To be honest, I agree with Ed Gillespie on this. Marketing’s marketing. It’s no more evil than language as a whole is evil. If you need to balance your karma, do some discounted work for a charity, or knock up a few free leaflets for your local bunch of hippies.

As for me? When the revolution comes, I’ll be writing the propaganda. 😉

Excellent post Tom. I went through something similar years ago and… well, in the end I told myself that what I do is okay. Because it is. Not least because I’ve never worked for ‘bad guys’. The nice thing about working in provincial ad agencies is that you’re not very likely to get that tobacco account selling fags to kids in Africa.

On the whole then I agree with Andy above…

“The nice thing about working in provincial ad agencies is that you’re not very likely to get that tobacco account selling fags to kids in Africa.”

Agreed. Worst (ethically speaking) client I’ve had to deal with was a company who manufactured drill bits for companies like BP and Haliburton. As someone who doesn’t drive, tries to save energy and likes to offset carbon where possible, that could’ve been a dilemma.

This is really interesting. A lot of copywriters seem to get into more for the writing and less for the marketing. I’m not sure if marketing is justified, but I think it’s vital to always be honest. People will always use rhetoric, but that’s only a bad thing if it’s misleading.

The best thing about working for yourself is that you get to pick and choose what you work on. Not so if you work for a big agency. I’ve done a lot of thinking about this recently – I had a client who is involved in an event, held where I live, that ethically I don’t really agree with. I worked on something different (and unrelated) for him, but decided that if he came back to me and wanted me to do some copywriting for this event, I’d have to very politely say no. I’m okay with that, there’s always another job.

I try not to think too hard about such things, because that way madness lies. Ethical dilemmas are everywhere you look.

This is beautifully, beautifully written. Thank you.

Thanks for the kind words.

An interesting piece, though as you said there is a glaring contradiction.

I’d say marketing is not inherently evil. Not all advertisements cajole people in unhealthy or unethical ways. An advert for Coca-Cola is IMHO not evil, yet I’d concede some others are (,,i.e. fashion adverts).

As a digital strategist/freelance copywriter, I guess this is an issue I (and ALL copywriters as we are marketing professionals by definition) must contend with, but then I think given the nature of humanity people will always misuse things. I say we are marketing professionals since advertising is a marketing communications tool, and like all marketing inputs is tailored towards target market needs (if anybody disagrees, well isn’t listing benefits, writing tone, etc. geared towards what target markets value?)

Marketing is not all evil, and the unscrupulous actions of a few shouldn’t tarnish all of us. I know also that some may challenge me on this in my line of work, but then I’d assert that any tool can be misused. Blame human nature, not marketing professionals. 😉

Thanks for the comment.

I think one could definitely argue that Coca-Cola ads are evil. The product has a host of health dangers (http://killercoke.org/health_issues.php ) and is squarely marketed at children who can’t deal with it (caffeine, tooth decay). Arguably, it’s on a health-risk continuum with cigarettes, ads for which are banned in the UK.

The cigarette example proves that when human nature is likely to bring people into danger, governments should legislate to protect them. Yes, it is very difficult to know where to draw the line, but it’s too easy to fall back on principles of ‘freedom’ just because the issues are complex or it’s difficult to establish causality.

‘What markets value’ is a slippery economist’s perspective that intellectualises the idea of ‘benefits’ while neglecting human nature. As Daniel Kahneman has shown, we make decisions emotionally (System 1), then rationalise them after the fact (System 2). Advertisers are very much interested in manipulating System 1 to establish an emotional link with their products. From this psychological perspective, we can’t really talk about ‘what markets value’ as a prior reality, because the notion of value can be created or altered by marketers – indeed, that’s their sole aim. So while you certainly can’t sell snow to eskimos, you can certainly cultivate a need in a receptive audience. If you couldn’t, nobody would be doing any marketing at all.

Thanks again for the comment.

Wow, this really speaks to me. Thanks for writing this. I am a graphic designer who started my job wanting to design beautiful things. More and more lately, I am becoming a marketer. I have been able to rationalize it somewhat with the “careerist” attitude for the past year, but lately it’s getting hard as I dive deeper down the rabbit hole. It’s time for me to examine where I’m headed, but it seems in this day and age, a practical artistic job like graphic design is inherently entwined with marketing and it’s many arms. Thanks for your well thought out article. You’ve articulated what I know to be true in my heart.

Thanks for the kind words. I’m glad you found the piece valuable. I don’t have any answers on how to reconcile these ideas with a marketing-based career, but I think it does help to at least think through the issues…

Tom,

You have beautifully articulated a recurrent theme in my own thoughts. I am a young marketer, originally from the social sciences, and I love the field for the combination of creativity and analysis.

I know I will do things that do not sit well with me. The day I flog bottled water will be the day I die a little inside. And yet… It is a toolbox. It is neutral in a way. It is inevitable, and like the Hydra, if not me, someone else will spring up in my place.

I will one day sell that bottled water. And without opening a huge can of worms, I am at the moment convinced that capitalism within liberal democracy is the most sustainable (ironically) form of organising society and its resources without civil conflict or government oppression.

But it is important to retain your soul, and be reflective, and think about the morality of your actions. I can’t really reconcile my views either, except to hope to be a force for change from within the business world, but I’m nevertheless grateful for this article.

I’d love to chat sometime, to you or anyone else who is interested in the topic.

sebastian.roberts.brown@gmail.com

Thanks for the kind words!

No one keeps a moral or ethical score on you, just a credit score.

I will hide comfortably behind, “There are bills to pay…” or one of the arguments above and retire with any moral or ethical dilemmas safely tucked under the self-suppression rug.

There’s nothing under there, I am simply doing my job.

Hash tag smiley face, Hash tag if it feels good you should buy it then moron.

Either be a part of the solution or be a part of the problem. It’s that simple. Just leave. Life is too short to waste doing something that deep down you feel is wrong. I think you’ve articulated brilliantly some of the stories people tell about why it’s ok to just accept the status quo. This taps into a deeper kind of conditioning that there is no point trying to change anything, or to do good. Is it ok to work on accounts for Nike, Nestle, Shell, Coke or any brand that is involved in slave labour, environmental disaster or other health or ethical concerns? I say it isn’t, and society won’t change until we leave that persuasive manipulative nonsense behind. There is a function of advertising which is inherently useful and informative. It’s good to know about the people behind the company and their supply chain, and about the product or service itself so we can make an informed choice. That is a different area, and useful constructive businesses can and should be effectively presented to their audiences. But really how many intelligent internet-savvy people really buy into marketing’s illusions, except perhaps sometimes to align with an ideology? Personally, I don’t trust politicians, marketers, shops or corporations to provide useful information. The only thing holding the insatiable need for profit back is litigation (it is clear that this makes, for example, a mockery of labels like fair trade where child labour is still being used to source cocoa).

I read peer reviews (affiliate marketing reviews are so insidious) and do my own research. I believe that’s what we really need. Trust, quality and authority in our sources of information. In the UK I have always sensed a kind of classist attitude that accepts the idea that it’s ok to exploit the less-educated and more susceptible people. As long as we’re making money, who cares?

Having worked in digital agencies for many years, I have seen these types of attitudes. The knowing clever cynicism, the design fetishism that justifies its existence at all costs, the totally apathetic attitude towards any sense of real connection with the thing being marketed, and a general culture of hedonism and arrogance that exists in a kind of spiritual vacuum. I have come to believe that many people in these agencies couldn’t care less about global politics and understanding the darker side of capitalism. If you are intelligent and sensitive, with a sense of ethics and compassion for society and humanity as a whole, I would say; it’s almost a duty to stop wasting your precious time working for morons and do anything you can to make a positive impact in the world. It is only us who are capable of making a difference.

Which opens the debate: Is marketing evil or are some marketers evil?

Thanks for the thoughtful article 🙂 I’m a fourth year marketing student and occasionally the question “Is marketing evil?” will drive me a little nuts. But, most the time I’m just worried about getting a job to begin with!

Thanks for the thoughtful article 🙂 I’m a fourth year marketing student and occasionally the question “Is marketing evil?” will drive me a little nuts. But, most the time I’m just worried about getting a job to begin with! Any advice?

What you don’t have, you don’t miss – at least that is until the marketing/advertising industry tells you otherwise. This is a very interesting piece of writing from someone on the ‘inside’, who must know what he’s talking about.

I’ve been thinking about this idea that late stage capitalism has to keep finding new ways for people to over-consume, in order to keep the economy ticking. Do you think we’ll ever get to the point where we’ll start making things that don’t have built-in obsolescence designed into them, but instead demand more robust products? I’ve just discovered that a young designer called Tom Cridland, is selling a 30 year range of clothes over the Internet and in his shop in the Kings Road. A thirty year T-shirt will set you back £35 – from an accountant’s perspective, that represents remarkable good value for money. I can also recall reading about the Soviet Union’s Saturnas indestructible vacuum cleaner. It may have taken the average Soviet citizen three years to save up for one, but once bought it apparently never broke!

Of course, a low consumerism society doesn’t leave much room for the marketers and advertisers to ply their trade. What would guys be doing instead?

Nice piece Tom.

The fact is that we are now so technologically successful as a species that we could all have our needs met with minimal effort (each person maybe ‘working/labouring’ for a couple of hours a week). We could all have most of our time free to play, create art/pursue meaningful activities. But this doesn’t support hierarchical power structures. If human’s predominantly cared about truth, beauty, love and art, and our ecosystem, we couldn’t be manipulated against our self interest to spend our lives producing and consuming in order to maintain an economic elite and top down feudal political systems.

Marketing helps support the capitalist mythology we all labour under and sustains the ongoing sublimation of human energy into self-destructive behavioural patterns.

Sigh.

The utopia argument. The Pilgrims tried this when they came to America. They all decided that the most loving and moral way to live was to communize all of their food resources into a giant pot, but that’s now how life works…or has every worked — 3/4 of Plymouth died after the first year. They then decided to make each person responsible for their own plot of land and survival; everyone survived and created a bounty of food.

The bottom line? Humans ALWAYS have to prove their worth to exist on this planet. There is no magic society where no one has to work, or only has to work for a few hours. If that society were to exist, it would require mass coercion of every single person to give to others (talk about immoral and un-lovingly selfish) and to strip them from their own autonomy to live their own life as they see fit. No one has the physical right to come up to a cattle rancher that has been breeding his own flock and building his own home and family and then telling him that he needs to give to others because other’s have less. While giving to others is admirable and a desired trait, the idea that people are “owed” is incredibly self-serving in the name of comfort. What if I created a concoction of immortality from the sweat of my own brow and I decided it wasn’t something I was willing to sell. Do the people have the right to barge down my door in the name of “love and destroying power structures” and take as they please? Seriously, the ends always justify the means with all these utopia arguments, and it’s incredibly frustrating and shows an incredible lack of understanding of the depth of ethics. Peace, love, and happiness is not ethics and morality; a lot of times what seems to be the most loving decision is the least moral action to take. Ethics are incredibly complex and require years of intense study and a common accepted moral framework of society.

Millions of people have died in the name of utopia. People have also died under capitalism, but they always have autonomy to live. Sometimes people grow up in broken families, which unfortunately is a burden that is passed on to their children, but someone along the way of their made the choice to use their freedom as they see fit (which is why divorce used to be a huge taboo). Nowadays, people look at successful families that remained responsible for generations and then decided it’s not fair that their forefathers didn’t fail much like their own families. As a result, broken families demand support for government, government grows, successful people are torn down (much like all the successful farmers in Soviet Russia that were slaughtered) and then EVERYONE’S ability to build themselves up (which may take several generations – it’s not a “right” to be happy and comfortable within one’s lifetime) is destroyed in the name of universal happiness and an abundance of free-time, free-love, and free-pleasure.

Marketing doesn’t support capitalism any more than sex supports prostitutes. They are both a function of the choices a society makes, which is precisely why at the very beginning of the industrial revolution we were warned that society could only subsist under the purview of Christian ethics in order to control for run-a-way capitalism. No one is willing to look at themselves and their own behavior anymore, rather, they just blame it on the “system,” or “the rich.” If you really want to throw your head for a spin, this “producing and consuming in order to maintain an economic elite” is EXACTLY what happens in an all “needs met with minimal effort” society. People think it doesn’t and then advocate for higher taxes in the name of EVERYONE living a comfortable and happy life and every single time the very people that demand more taxes strip the ability of others to free themselves by the sweat of their own brow as it becomes impossible for anyone other than the very wealthiest individuals to pay taxes and also living independently. As such, the elite power structure is born in the name of universal happiness. Please see Venezuela for the most current example of this and we’ve been on the same trajectory in America for close to 100 years now (graduated taxes is straight from the communist manifesto).

The only system to balance run-a-way capitalism is run-a-way freedom of low taxes and constraints, which necessarily requires people to fend for themselves. It’s a paradox that well meaning people simply cannot grasp because they are tempted to believe life is all about love, happiness, and pleasure; it is not. People have to earn that for themselves with the help of others in their communities.

Lastly, capitalism is only self-destructive if the people are self-destructive. No one needs a phone, car, computer, etc. to live. If more people grew their own food, made their own clothes, and became self-reliant as opposed to investing in entertainment and frivolous material pleasures, we’d all be much happier. The problem is, American’s aren’t willing to do so. Christianity talks about this at length, but we’ve long ago eschewed Christianity in the name of materialism. Capitalism is not the problem, sir. At it’s core, even the Amish practice capitalism when they trade goods and services for each other, which is the simplest form of what capitalism is: trading excess produced goods for another service of excess produced goods.

The real problem is materialism and people’s refusal to give up conveniences and pleasures. Women in particular are almost exclusively most guilty of this due to the need to so for women to “free” themselves economically (spending 80% of all monetary exchange each day), which is precisely why the communists advocated for women to vote, work, and spend: it grows government and creates a permanent hierarchy that can be shrouded in the name of peace, love, and happiness (the whole, ‘love always wins’ mantra is straight from the mouth of one of the most influential communist thinkers, please look it up for yourself).

You have a lot of reading to do sir, although, if what is happening in America now is a litmus test it may already be too late, and unfortunately, the very people that think what they’re doing is morally justified and “right,” will be enslaving themselves both literally and mentally in painstaking regret and destruction. I have many American who’s parents are grandparents are trying to get BACK to Russia and all of them say the exact same thing: “What’s happening now is EXACTLY what was happening at the beginning of the USSR.” People have no idea what they’re doing.