The consumer is your husband

The consumer isn’t a moron; she is your wife.

David Ogilvy, Confessions of an Advertising Man

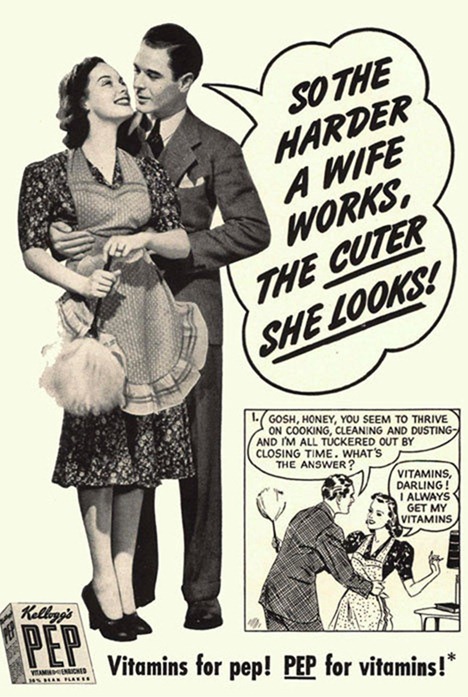

As well as capturing a timeless truth about marketing, this famous line also tells us a lot about the era when it was written.

On the one hand, it reflects a new respect for ‘the consumer’. When Confessions of an Advertising Man appeared in 1963, a creative revolution was beginning. Inspired by the pioneering work of Bill Bernbach, advertising became much more playful, daring and intriguing. Ads began to treat the reader as an intellectual equal and an accomplice in the creation of meaning – not just a ‘moron’ who could be easily manipulated with tricks and bribes.

However, Oggers’ blithely sexist language shows that his world was still one where ads were created by men for women. It is the world portrayed so vividly in Mad Men. While women may have seen more interesting ads as a result of Ogilvy’s thinking, they were still being tossed those ads by an overwhelmingly male ad industry – and for purely commercial motives, not to further their liberation.

Plus ça change

Fifty years on, it would be nice to think everything had changed. But while more men do the shopping now, it’s a different story when it comes to making the ads. Witness the 3% Conference, an event/movement aimed at increasing the proportion of female creative directors from the pitifully low level of, yes, just 3%.

Clearly, there are lots of female copywriters, art directors and client-facing staff out there. But the 3% statistic has a significant implication for the creative process as a whole. It means that while ads created, nurtured and signed off exclusively by men are commonplace, their ‘all-female’ counterparts must be vanishingly rare – even for products aimed exclusively at women.

Why does that matter? The obvious reason is the principle of equality. Unless there is some objective reason why people of one gender can do a particular job better, we should see equal numbers of men and women performing that role. If we don’t, we rightly suspect prejudice or discrimination in the workplace.

False equivalence

At this point, fools sometimes try to claim that there are fewer female creatives (or comedians, or whatever) because their abilities are inferior. ‘If women had more talent, they’d get more gigs,’ they say.

This argument is based on false equivalence. It pretends, disingenuously, that because men can succeed on merit, we live in a meritocracy. And it inverts cause and effect by implying that women’s lives are the reason for their place in society, rather than the result of it.

In reality, opportunity is far from equal. If you doubt it, read this post by James Chartrand, a female freelance copywriter who started getting far more work the second she adopted her masculine nom de plume. I’m sure many other female creatives can tell stories of dismissive attitudes, glass ceilings and low salaries.

The power of patriarchy

Most businesses, including marketing agencies, are inherently patriarchal. Women work there, but the institutions themselves are predominantly owned and controlled by men. As a result, they have ‘masculine’ cultures, in which it’s far more difficult for women to gain recognition and advancement.

This, in turn, generates perceptions of female inferiority, establishing a vicious circle that men have little incentive to break – at least in terms of narrow self-interest. In this way, patriarchies sustain themselves until they meet a sufficiently powerful challenge. (Of course, women can also be complicit, but I’m not even going there in this short post.)

From this perspective, it’s clear that box-ticking exercises like fulfilling gender quotas, or arbitrary gestures like making Starbuck a woman, are not enough. They are the starting point, not the finishing line. Ultimately, our culture needs to be profoundly and radically feminised in ways that are difficult to imagine, let alone achieve.

Women are the superset

With those principles firmly established, let’s look at the issue from a commercial perspective. Does gender imbalance affect agencies’ ability to reach female consumers? As with the UK Parliament (around 20% female), we have to ask ourselves whether an organisation with such a wildly anomalous gender profile can credibly claim to represent, or communicate with, the wider population.

For 3% founder Kat Gordon, the disadvantages are crystal clear. This quote from her is taken from the conference’s about us page:

There are only three consumer categories where men dominate purchases, yet agencies still talk about ‘women’s accounts’ as mops and makeup. The truth is that women are the superset, not the subset, and the rate at which women are amassing wealth and exerting influence is unprecedented. Yet the work that is supposed to motivate them springs almost entirely from a male perspective. The advertising business is a $33 billion industry. Misunderstanding female consumers, from a business perspective, is sheer lunacy.

Who you are vs what you know

Kat’s position is that men can’t understand women, and therefore can’t sell to them. Is she right?

When I’ve asked ‘can men write for women?’ online, I’ve usually received bullish responses such as ‘anyone can write for anyone’. The idea is appealingly simple and liberal, but ultimately too reductive.

The more complex reality is that a writer’s empathic potential in a given situation is determined by their unique knowledge and background rather than their identity. It’s not who you are, but what you know – and gender plays an important part.

The blunt query ‘can Gender A write for Gender B?’ obscures the fine but crucial distinction between gender and experience. It’s not that your gender disqualifies you from writing about particular products. Rather, your unique experience of life determines the level of insight you bring to a brief. And your experience, for better or worse, is largely determined by your gender.

Method writing

Copywriting is a bit like method acting. If you want to play someone, or write something that will appeal to them, you have to step into their shoes. And copywriters, like actors, have limits to their range, and areas where they’re more comfortable or knowledgeable. (Robert Downey Jr’s absurd blackface performance in Tropic Thunder played with the idea of an actor pushing the envelope way too far.) The wider a copywriter’s experience, the more people and situations they can relate to – which is one reason why you might prefer a seasoned plodder over a hip young gunslinger.

This year, I’ve written about two products aimed exclusively at women: a cosmetic face mask and a range of yoga and fitness clothing. I was flattered to be asked, and I relished the challenge. In the event, though, I could only get about 95% of the way to a viable text without help from my two respective clients (both female). One noted amusedly that I ‘wrote like a man’, while the other gently pointed out that some of my word choices, while descriptively accurate, just weren’t right.

I didn’t fall short because I was a man. And I didn’t fall short because there is some ineffable core to the experience of femininity that I can never understand – although there may be. I may have fallen short because I’m a crap writer, but let’s ignore that for the sake of argument. The main reason for my falling short is that I didn’t have enough experience of the products – which was an indirect consequence of my being a man in a society like ours.

Insight is everything

Had my life been different, the result have been different. If I’d previously worked behind a cosmetics counter, or as a personal trainer, I might have far more insight into the way women choose, use and describe the types of products I was writing about. But I haven’t, and I’m betting that relatively few male copywriters have. Conversely, I would imagine that a significant proportion of female copywriters would have first-hand experience of the category. These are factual observations, not value judgements or gender discriminations.

There should be as many female creatives as male. Even if the principle of equality weren’t enough on its own, the commercial argument is unanswerable. Your ability to communicate with people is directly linked to your insight into their experience – and you can’t sell to people you know nothing about.

Comments (18)

Comments are closed.

So, as I would always expect from your posts, this was all very true – and fascinating.

But the James Chartrand story always makes me think about the diversity of clients, what they know, and what they think they want.

The truth is we’re salesmen. And right away that’s masculine. On that note, it doesn’t surprise me to see women undervalued.

But sometimes you get clients who want emotion. Or storytelling. Or a sense of luxurious glamour.

I wonder if those clients would actively prefer a female writer to a male one?

Always an interesting area to think about.

Hi Tom, great blog post as always.

I have some questions that I have been thinking about since I first heard about the 3% Conference the other week. Maybe you (& others) can enlighten my young naive self.

Can women write good ads for women? Have women have become so accustomed to viewing advertising & media aimed at them from a male perspective that even female creatives would struggle to write good copy aimed at their own gender?

You mention insights & first hand experience that female copywriter might have that her male counterparts don’t. But as women, aren’t we are consumers in the environments constructed by males? So isn’t that experience slightly artificial?

I ask these questions because I’m questioning my own progression into a creative career. I see at adverts aimed at women and I find the majority of them appalling. But when I think of how I would change them to appeal better to me as a women, I struggle and end up thinking like a “man” because I can’t seem to break away from the kind of advertising that I’ve grown up with.

The majority of people I’ve worked for so far have been men. There don’t seem to be many women do there?

Gillian

“At this point, men’s rights fools sometimes try to claim that there are fewer female creatives (or comedians, or whatever) because their abilities are inferior. ‘If women had more talent, they’d get more gigs,’ they say.”

No they don’t. They say that – largely – there are societal reasons for it, some of which are actually embraced by the majority of women. Attacking Mens’ Rights Activists is pathetic. Fundamentally, the Mens’ Rights Movement is about equality.

“At this point, men’s rights fools sometimes try to claim that there are fewer female creatives (or comedians, or whatever) because their abilities are inferior. ‘If women had more talent, they’d get more gigs,’ they say.”

Nobody actually says that. With all the straw you’re tossing around, no wonder you’re a stuffed shirt.

The reference to Mens’ Rights was flippant and not relevant to my argument, and I had actually intended to take it out, so I’ve now made this change. That doesn’t indicate that I agree with you about the movement.

Insulting me from behind an anonymous username? Stay classy.

Your question is pretty wide-ranging and I’m not sure I’m really qualified to answer it. I’d certainly agree that ads generally lean on stereotypes, both male and female – hopeless dad, busy mum etc – and these stereotypes do seem remarkably resilient.

Having said that, there has been a lot of progress. The ad I’ve included above would be absolutely unthinkable today. If you look at ads from the 70s and 80s, for example in the beer category, you’ll see sexism bordering on outright misogyny that, again, would not get on the screen today. So while the surrounding structures may still be patriarchal, as I’ve argued, that doesn’t mean that things can’t change incrementally or locally.

I’m not really an ad writer, but I imagine the answer will lie in communicating as simply, directly and honestly as possible, without recourse to any sort of ‘angle’, borrowed interest or stereotype that would take us back to what already exists. That takes talented creatives and clients brave enough to approve the work. A tall order, but progress is possible, or we would still be looking at ads about getting the maximum amount of housework out of your wife.

Thanks for this great write-up, Tom. I want to make one thing clear to your readers: I actually don’t believe that men can’t market to women. Nor do I believe that women can automatically do it well because of their gender. I state this overtly in my presentations. What I do believe is that a 97% skew — towards anything — creates groupthink that will never, ever unlock the best creative output. Many of your observations about the fluency of writing to a group you understand I agree with. I had to work far, far harder when I was a copywriter at Sports Illustrated and PowerBar, writing to appeal to cyclists and football fans, than when I wrote about new motherhood for Target shortly after my own kids were born.

Don’t dish it out if you can’t take it.

Great article, thank you Tom. I always worry when I start reading gender-related pieces that I’m going to hear the same old same old – yours is most refreshing. I couldn’t agree more that it’s experience, imagination and insight that will get the job done. I moved from London to Bristol and am happy to say that there seem to be comparatively more female writers here.

I said your argument was a strawman. That is a real charge and not an insult. You chose not to address it by which I take it that you agree with the charge.

Also, fuck off.

If you’d made your point politely, ‘Rog’, I would have been more inclined to engage with you. It’s your attitude, rather than the strength of the insult, that’s the point here. Or I am I supposed to be grateful that you didn’t call me something worse?

The ‘women aren’t funny’ narrative is so commonplace, so wearyingly familiar, that I didn’t even bother referencing it. If you Google that phrase you will get over 100m results.

In the workplace, the notion of women’s inferior ability is borne out by unequal pay grades, glass ceilings and many other depressing phenomena that have been exhaustively chronicled at great length elsewhere. If men aren’t saying these things, they’re certainly thinking them and acting as though they were true. They are attitudes that prevail in our society, regardless of how and when they’re actually articulated.

I see, you’re defending the statement now by focusing in on the parenthetical.

And saying you are poking holes at strawman and a stuffed shirt is clearly way more polite than your general tone in your essay.

“At this point, men’s rights fools”

So moron, heal thyself.

Jesus Christ Tom, did you or an associate truly write this?

“Good copywriting makes the difference between building bridges and burning them.”?

Bwa-ha-ha-ha-ha

I’ve just deleted a long, bad-tempered comment exchange that was sparked off by an offhand reference to the Men’s Rights movement in the original post. The reference wasn’t appropriate or relevant to my argument, so I deleted it. I’m also removing the related discussion since it referred to a point I was happy to retract, and took the discussion way off topic.

As if to disprove my comment yesterday about things getting better, the ad below appeared on page 21 of today’s Irish Independent. It was shared on Twitter by Christine Bohan via Holly Brockwell.

It’s hard to believe this actually ran. ‘We’ refers to men, implicitly excluding the female reader. The wife is equated with a car, positioning her as a chattel who can be given away or traded by a male ‘owner’. And the premise of the whole thing is so unbelievably crass that it will (or should) alienate car buyers both male and female.

What a super, thoughtful post. And what a delight that it came from a man. Equality is everyone’s business, and I think a lot more men would speak up for equality if people realised that it cut both ways.

At the same time women feel restricted in the workplace, I think men often feel restricted at home. They’re bombarded by messages that imply that women are the only ones who can properly raise the children or run the home. My brother-in-law is a stay-at-home dad; my sister-in-law is the one with the career. S has put his career – which he loved – on hold to bring up their daughter. M has a great career and brought in better, steadier money. I haven’t ever really talked to them about it, but I guess that in itself says that it’s never been an issue. Everyone is certainly very happy.

When attitudes change towards men staying at home, I think things will begin to get easier for women at work.

We’ve got a long way to go in every area. This is something that I’m thinking more and more about these days, and I think it’s the way my career is eventually going to turn. It’s incredibly important.

Have you read Lean In by Sheryl Sandberg? If you haven’t, you should. It’s brilliant and thought-provoking.

Thanks for the post!

Thanks for the kind words! I’ll add Lean In to the book-list of shame…